Appendix 6h: Adult Social Care safeguarding flags

|

VAWG Flag

|

Abuse Types

|

|

Controlling or Coercion

|

Coercion And Control; Harassment; Psychological/Coercion And Control; Restraint; Verbal Abuse

|

|

Domestic Abuse

|

Domestic Abuse; Other Domestic Abuse

|

|

Economic Abuse

|

Financial; Financial & Material; Financial And Material; Misuse Of A Legal Authority; Misuse Of Financial Affairs By A 3rd Party; Other Financial & Material; Rogue Trading/Scamming; Theft

|

|

Emotional and Other Abuse

|

Emotional / Psychological; Harassment; Hate Crime; Mate Crime; Other Discriminatory; Other Psychological/Emotional; Psychological / Emotional; Psychological/Emotional; Verbal Abuse

|

|

FGM

|

FGM; Sexual Abuse FGM

|

|

Forced Marriage

|

Forced Marriage

|

|

Honour-Based Violence

|

Honour Based Violence; Honour-Based Violence

|

|

Physical / Sexual Abuse

|

Assault; Other Physical Abuse; Other Sexual Abuse; Physical; Physical Abuse; Sexual; Sexual Abuse; Sexual Abuse FGM

|

|

Sexual Exploitation

|

Sexual Exploitation

|

|

Sexual Violence

|

Other Sexual Abuse; Sexual; Sexual Abuse; Sexual Exploitation

|

|

Stalking and Harassment

|

Harassment; Verbal Abuse

|

|

Violence

|

Assault; Inappropriate Physical Sanctions; Physical; Physical Abuse; Restraint

|

[1] The London Borough of Camden. We Make Camden: About. [Internet]. London: The London Borough of Camden; [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.wemakecamden.org.uk/about/ [[We Make Ca…orough …]](https://www.wemakecamden.org.uk/)

[2] London Borough of Camden. Camden Community Safety Partnership. [Internet]. London: London Borough of Camden; [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.camden.gov.uk/camden-community-safety-partnership [[Free Vanco…5] - MyBib]](https://www.mybib.com/tools/vancouver-citation-generator)

[3] United Nations General Assembly. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women: resolution adopted by the General Assembly. New York: United Nations; 1993 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/179739?v=pdf

[4] London Borough of Camden. We Make Camden Vision. London: London Borough of Camden; 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.wemakecamden.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/We-Make-Camden-Vision.pdf

[5] London Borough of Camden. Camden Community Safety Partnership Plan 2024–2027. London: London Borough of Camden; 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.camden.gov.uk/documents/d/guest/camden-community-safety-partnership-plan-24-27-2-

[6] United Kingdom. Domestic Abuse Act 2021, Part 4. London: The Stationery Office; 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2021/17/part/4

[7] Office for National Statistics. Domestic abuse victim characteristics, England and Wales: year ending March 2024. Newport: ONS; 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabusevictimcharacteristicsenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2024#sex

[8] United Nations General Assembly. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women: resolution adopted by the General Assembly. A/RES/48/104. New York: United Nations; 1993 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.refworld.org/legal/resolution/unga/1993/en/10685.

[9] World Health Organization. Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018. Geneva: WHO; 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256

[10] World Health Organization. Violence against women: fact sheet. Geneva: WHO; 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

[11] See reference 10

[12] See reference 10

[13] World Health Organization. RESPECT women: Preventing violence against women. Geneva: WHO; 2019 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-RHR-18.19

[14] United Kingdom. Domestic Abuse Act 2021: full contents. London: The Stationery Office; 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2021/17/contents

[15] HM Government. Tackling violence against women and girls strategy. London: Home Office; 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6194d05bd3bf7f054f43e011/Tackling_Violence_Against_Women_and_Girls_Strategy_-_July_2021.pdf

[16] Office for National Statistics. Crime in England and Wales: year ending March 2022. London: ONS; 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/crime-in-england-and-wales-year-ending-march-2022

[17] National Audit Office. Tackling violence against women and girls. London: NAO; 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/tackling-violence-against-women-and-girls.pdf

[18] National Police Chiefs’ Council. Call to action as violence against women and girls epidemic deepens. London: NPCC; 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://news.npcc.police.uk/releases/call-to-action-as-violence-against-women-and-girls-epidemic-deepens-1

[19] Office for National Statistics. Domestic abuse victim characteristics, England and Wales: year ending March 2024. Newport: ONS; 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabusevictimcharacteristicsenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2024#sex

[20] Camden Women’s Forum. Domestic violence and abuse inquiry report. London: London Borough of Camden; 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://democracy.camden.gov.uk/documents/s109414/Appendix%20B%20-%20Camden%20Womens%20Forum%20domestic%20violence%20and%20abuse%20inquiry%20report.pdf

[21] Women’s Aid Federation of England. Investing to save: the economic case for funding specialist domestic abuse support. Bristol: Women’s Aid; 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://imece.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/womens-aid-investing-to-save-report-2023.pdf

[22] Women’s Aid Federation of England. The Price of Safety: The cost of leaving a perpetrator and rebuilding a safe, independent life. Bristol: Women’s Aid; 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.womensaid.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Price-of-Safety-Report-2024-Final-Version.pdf

[23] London Borough of Camden. We Make Camden Vision. London: London Borough of Camden; 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.wemakecamden.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/We-Make-Camden-Vision.pdf

[24] United Kingdom. Domestic Abuse Act 2021: c.17. London: The Stationery Office; 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2021/17/contents

[25] HM Government. Tackling violence against women and girls strategy. London: Home Office; 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6194d05bd3bf7f054f43e011/Tackling_Violence_Against_Women_and_Girls_Strategy_-_July_2021.pdf

[26] United Kingdom. Equality Act 2010: c.15. London: The Stationery Office; 2010 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents

[27] Home Office. Tackling Domestic Abuse Plan. London: HM Government; 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/tackling-domestic-abuse-plan

[28] United Kingdom. Online Safety Act 2023: c.50. London: The Stationery Office; 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2023/50/contents [[Online Saf…ion.gov.uk]](https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2023/50/contents)

[29] Domestic Abuse Commissioner. We must build on the Online Safety Act to ensure all victims are protected from online abuse [Internet]. London: Domestic Abuse Commissioner; 2023 Dec 19 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://domesticabusecommissioner.uk/blogs/we-must-build-on-the-online-safety-act-to-ensure-all-victims-are-protected-from-online-abuse/

[30] United Kingdom. Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004, Part 1, Domestic homicide reviews. London: The Stationery Office; 2004 [cited 2025 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2004/28/part/1/crossheading/domestic-homicide-reviews.

[31] Home Office. Tackling Domestic Abuse Plan. London: The Stationery Office; 2022. CP 639. ISBN: 978-1-5286-3279-9 [cited 2025 Oct 10]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1064427/E02735263_Tackling_Domestic_Abuse_CP_639_Accessible.pdf.

[32] Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Homelessness code of guidance for local authorities. GOV.UK; 2018 [updated 2025 Jul 18; cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/homelessness-code-of-guidance-for-local-authorities

[33] Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Improving access to social housing for victims of domestic abuse. GOV.UK; 2018 [updated 2025 Jul 10; cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/improving-access-to-social-housing-for-victims-of-domestic-abuse/improving-access-to-social-housing-for-victims-of-domestic-abuse

[34] Department of Health and Social Care. Women’s Health Strategy for England. GOV.UK; 2022 [updated 2022 Aug 30; cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/womens-health-strategy-for-england

[35] UK Parliament. Sexual Offences Act 2003: Chapter 42. Legislation.gov.uk; 2003 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/42/contents

[36] UK Parliament. Protection from Harassment Act 1997: Chapter 40. Legislation.gov.uk; 1997 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1997/40/contents

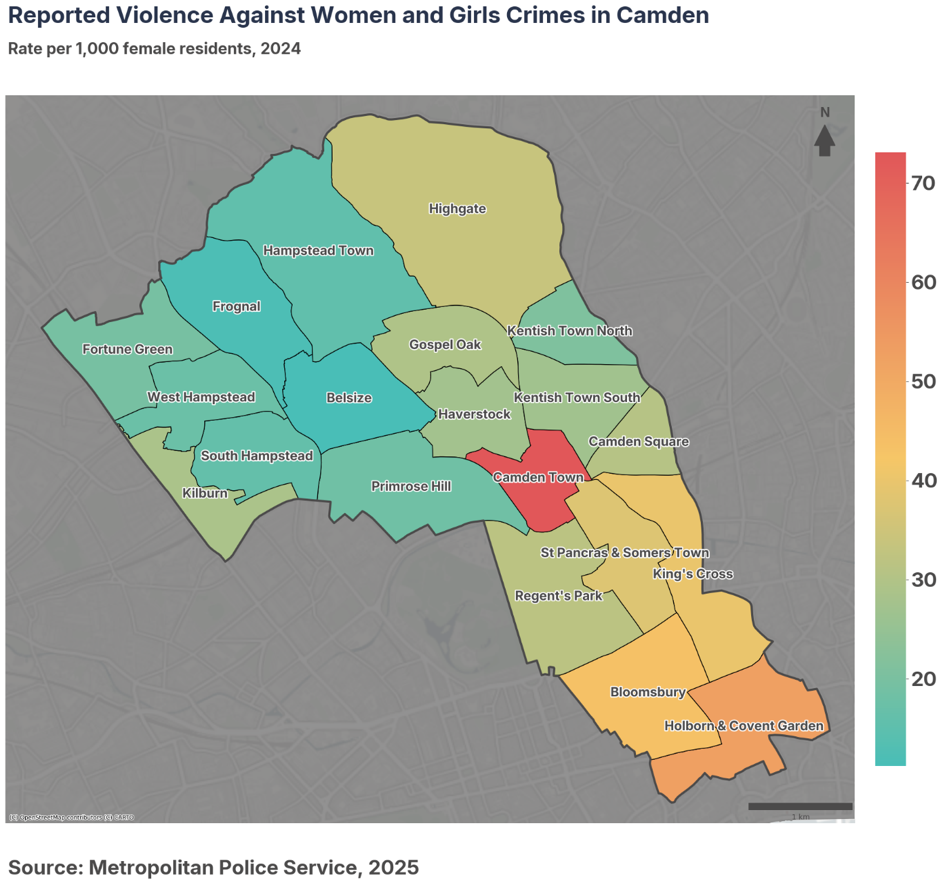

[37] UK Parliament. Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003: Chapter 31. Legislation.gov.uk; 2003 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/31/contents [[Female Gen…ion.gov.uk]](https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/31/contents)

[38] UK Parliament. Modern Slavery Act 2015: Chapter 30. Legislation.gov.uk; 2015 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/30/contents

[39] Greater London Authority. Tackling violence against women and girls: The Mayor’s strategy for London 2022–2025. London City Hall; 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.london.gov.uk/publications/tackling-violence-against-women-and-girls [[Tackling V…City Hall]](https://www.london.gov.uk/publications/tackling-violence-against-women-and-girls)

[40] Greater London Authority. Domestic abuse safe accommodation and support: The Mayor’s strategy for London 2025–2028. London City Hall; 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.london.gov.uk/programmes-strategies/housing-and-land/mayors-priorities-londons-housing-and-land/domestic-abuse-safe-accommodation-and-support

[41] Home Office. Domestic Abuse Act 2021: Statutory Guidance. GOV.UK; 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7f850940f0b6230268ffba/DometicAbuseGuidance.pdf

[42] Royal College of Nursing. Domestic abuse: Guidance for nurses, midwives, and health care professionals. RCN; 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.rcn.org.uk/-/media/Royal-College-Of-Nursing/Documents/Publications/2023/November/011-242.pdf

[43] National Police Chiefs’ Council. Policing violence against women and girls – The national framework for delivery: 2024–2027. NPCC; 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.npcc.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/media/downloads/our-work/vawg/vawg-framework-for-delivery.pdf

[44] Gibbs A, Dunkle K, Ramsoomar L, Willan S, Jama Shai N, Chatterji S, Naved R, Jewkes R. New learnings on drivers of men’s physical and/or sexual violence against their female partners, and women’s experiences of this, and the implications for prevention interventions. Glob Health Action. 2020;13(1):1739845. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/16549716.2020.1739845

[45] Yakubovich AR, Stöckl H, Murray J, Melendez-Torres GJ, Steinert JI, Glavin CEY, Humphreys DK. Risk and protective factors for intimate partner violence against women: Systematic review and meta-analyses of prospective–longitudinal studies. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(7):e1–e11. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304428

[46] SafeLives. Spotlight on disabled people and domestic abuse. SafeLives; 2017 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://safelives.org.uk/resources-for-professionals/spotlights/spotlight-disabled-people-and-domestic-abuse/

[47] Centre for Women’s Justice. Life or death: Preventing Domestic Homicides and Suicides of Black and Minoritised Women. 2023 Nov [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5aa98420f2e6b1ba0c874e42/t/655639ddc55be306e7dfa5c5/1700149727418/Life+or+Death+Report+-+Nov+2023.pdf

[48] Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Women’s health: migrant health guide. GOV.UK; 2014 [updated 2021 Sep 21; cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/womens-health-migrant-health-guide

[49] Closson K, Boyce SC, Johns N, Inwards-Breland DJ, Thomas EE, Raj A. Physical, sexual, and intimate partner violence among transgender and gender-diverse individuals. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(6):e2419137. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.19137

[50] Deering KN, Amin A, Shoveller J, Nesbitt A, Garcia-Moreno C, Duff P, Argento E, Shannon K. A systematic review of the correlates of violence against sex workers. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(5):e42–e54. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301909

[51] Struyf P. To report or not to report? A systematic review of sex workers’ willingness to report violence and victimization to police. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2023;24(5):3065–3077. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380221122819

[52] Imkaan. The value of intersectionality in understanding violence against women and girls. Imkaan; 2019. Available from: https://eca.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Field%20Office%20ECA/Attachments/Publications/2019/10/The%20value%20of%20intersectionality%20in%20understanding%20violence%20against%20women%20and%20girls.pdf

[53] College of Policing. Interventions to reduce violence against women and girls (VAWG) in public spaces: Evidence briefing. College of Policing; 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://assets.college.police.uk/s3fs-public/2022-03/Interventions-to-reduce-VAWG-in-public-spaces.pdf

[54] Department of Health. Protecting People, Promoting Health: A public health approach to violence prevention for England. London: Department of Health; 2012 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/a-public-health-approach-to-violence-prevention-in-england

[55] Michau L, Horn J, Bank A, Dutt M, Zimmerman C. Prevention of violence against women and girls: lessons from practice. Lancet. 2015;385(9978):1672–84. Available from: Prevention of violence against women and girls: lessons from practice - The Lancet

[56] Waigwa S, Doos L, Bradbury-Jones C, et al. Effectiveness of health education as an intervention designed to prevent female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C): a systematic review. Reprod Health. 2018;15:62. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0503-x

[57] Jewkes R, Flood M, Lang J. From work with men and boys to changes of social norms and reduction of inequities in gender relations: a conceptual shift in prevention of violence against women and girls. Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1580–1589. Available from: From work with men and boys to changes of social norms and reduction of inequities in gender relations: a conceptual shift in prevention of violence against women and girls - The Lancet

[58] Department for Education. Relationships education (Primary). London: GOV.UK; 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/relationships-education-relationships-and-sex-education-rse-and-health-education/relationships-education-primary [[Relationsh…) - GOV.UK]](https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/relationships-education-relationships-and-sex-education-rse-and-health-education/relationships-education-primary)

[59] Department for Education. Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) (Secondary). London: GOV.UK; 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/relationships-education-relationships-and-sex-education-rse-and-health-education/relationships-and-sex-education-rse-secondary

[60] Fraser E. School-based approaches to tackling violence: Violence Against Women and Children Helpdesk Report HD40. London: Social Development Direct; 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.datocms-assets.com/112720/1713164027-ending-vawc-hd-40-school-based-approaches-to-tackling-violence.pdf

[61] Gainsbury AN, Fenton RA, Jones CA. From campus to communities: evaluation of the first UK-based bystander programme for the prevention of domestic violence and abuse in general communities. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:674. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08519-6

[62] College of Policing. Bystander programmes: evidence briefing. London: College of Policing; 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://assets.college.police.uk/s3fs-public/2022-03/Bystander-programmes-evidence-briefing.pdf

[63] Women’s Aid Federation of England. Tackling domestic abuse in a digital age: A recommendations report on online abuse by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Domestic Violence. Bristol: Women’s Aid; 2017 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.womensaid.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/APPGReport2017-270217.pdf [[Tackling d…omen’s Aid]](https://www.womensaid.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/APPGReport2017-270217.pdf)

[64] Hughes M. How technology can enable violence against women and girls. London: Centre for Emerging Technology and Security; 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://cetas.turing.ac.uk/publications/how-technology-can-enable-violence-against-women-and-girls

[65] Mayor of London. IRIS Programme – Identification and Referral to Improve Safety. London: Greater London Authority; [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.london.gov.uk/programmes-strategies/communities-and-social-justice/londons-violence-reduction-unit-vru/our-research/vru-evidence-hub/iris-programme-identification-and-referral-improve-safety

[66] Tarr S, Gupta A. Practitioner responses to children and young people involved in forced marriage. Child Abuse Rev. 2022;31(3):e2740. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2740

[67] Standing Together Against Domestic Abuse. Never again. Again: A review of health recommendations following domestic abuse-related deaths. London: Standing Together; 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: Health/DHR Report FINAL Version

[68] Murphy M. Written evidence submitted to the Public Accounts Committee: Tackling Violence Against Women and Girls. London: UK Parliament; 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/138224/html/

[69] Office for National Statistics. Perceptions of personal safety and experiences of harassment, Great Britain: 2 to 27 June 2021. Newport (UK): ONS; 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/perceptionsofpersonalsafetyandexperiencesofharassmentgreatbritain/2to27june2021

[70] Girlguiding. Girls’ Attitudes Survey 2020. London: Girlguiding; 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.girlguiding.org.uk/globalassets/docs-and-resources/research-and-campaigns/girls-attitudes-survey-2020.pdf

[71] Office for National Statistics. Nature of sexual assault by rape or penetration, England and Wales: year ending March 2020. Newport (UK): ONS; 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/natureofsexualassaultbyrapeorpenetrationenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2020

[72] Dubey S, Bailey A, Lee JB. Women’s perceived safety in public places and public transport: A narrative review of contributing factors and measurement methods. Cities. 2025;156:105534. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2024.105534

[73] Camden Women’s Forum. Domestic violence and abuse inquiry report. London: Camden Council; 2021. Available from: https://www.camden.gov.uk/documents/20142/0/11a+Camden+Womens+Forum+domestic+violence+and+abuse+inquiry+report.pdf

[74] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Domestic violence and abuse: multi-agency working. Public health guideline [PH50]. London: NICE; 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/PH50

[75] Karlsen S, Carver N, Mogilnicka M, Pantazis C. ‘Putting salt on the wound’: a qualitative study of the impact of FGM-safeguarding in healthcare settings on people with a British Somali heritage living in Bristol, UK. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e035039. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/10/6/e035039

[76] Molnar L, Chopin J. What works to reduce sex workers’ risk of crime victimization? A scoping review. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work. 2025;22(3):315–333. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/26408066.2025.2456758

[77] Kelly L, Westmarland N. Domestic violence perpetrator programmes: steps towards change. Project Mirabal final report. London and Durham: London Metropolitan University and Durham University; 2015. Available from: https://repository.londonmet.ac.uk/1458/1/ProjectMirabalfinalreport.pdf

[78] Camden Women’s Forum. Domestic violence and abuse inquiry report. London: Camden Council; 2021. Available from: https://www.camden.gov.uk/documents/20142/0/11a+Camden+Womens+Forum+domestic+violence+and+abuse+inquiry+report.pdf

[79] London Violence Reduction Unit. Islington and Camden VRU-funded parenting project. London: Greater London Authority; [no date]. Available from: https://www.london.gov.uk/programmes-strategies/communities-and-social-justice/londons-violence-reduction-unit-vru/our-research/vru-evidence-hub/islington-and-camden-vru-funded-parenting-project

[80] Russell K. What works to prevent youth violence: evidence summary. Edinburgh: Scottish Government; 2021. Available from: https://www.gov.scot/publications/works-prevent-youth-violence-summary-evidence/pages/3/

[81] London Violence Reduction Unit. Supporting children and young people impacted by domestic abuse – Bambu Project. London: Greater London Authority. Available from: https://www.london.gov.uk/programmes-strategies/communities-and-social-justice/londons-violence-reduction-unit-vru/our-research/vru-evidence-hub/supporting-children-and-young-people-impacted-domestic-abuse-bambu-project

[82] Domoney J, Fulton E, Stanley N, McIntyre A, Heslin M, Byford S, Bick D, Ramchandani P, MacMillan H, Howard LM, Trevillion K. For Baby’s Sake: intervention development and evaluation design of a whole-family perinatal intervention to break the cycle of domestic abuse. J Fam Viol. 2019;34(7):539–551. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10896-019-00037-3

[83] The For Baby’s Sake Trust. For Baby’s Sake: joint summary report. London: The For Baby’s Sake Trust; 2021. Available from: https://www.forbabyssake.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/FBS-1165-Joint-Summary-A4-v5.pdf

[84] Domestic Abuse Act 2021. Part 1 – Statutory Definition of Domestic Abuse. London: UK Public General Acts; 2021. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2021/17/part/1

[85] Lambeth Council. What is VAWG? [Internet]. London: Lambeth Council; [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/what-is-vawg

[86] Women’s Aid. How common is domestic abuse? [Internet]. London: Women’s Aid; [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.womensaid.org.uk/information-support/what-is-domestic-abuse/how-common-is-domestic-abuse/

[87] Crown Prosecution Service. Annex 1B: Table of offences – Scheme C Class Order [Internet]. London: CPS; [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.cps.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/legal_guidance/annex-1b-table-of-offences-scheme-c-class-order.pdf

[88] Metropolitan Police Data Analyst Team. Definition of violence against women and girls (VAWG) [email correspondence]. Message to: [Ruby Johnson]. 2025 Apr 29.

[89] Lambeth Council. What is VAWG? [Internet]. London: Lambeth Council; [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/what-is-vawg

[90] Women’s Aid. Halving what? Measuring VAWG [Internet]. London: Women’s Aid; 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.womensaid.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Halving-What_-Measuring-VAWG.pdf

[91] Domestic Abuse Commissioner. Briefing from the Domestic Abuse Commissioner for England and Wales: Home Office Counting Rules [Internet]. 2024 Apr [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://domesticabusecommissioner.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2404-Home-Office-Counting-Rules-Briefing-from-the-Domestic-Abuse-Commissioner.pdf

[92] London City Hall. Mayor announces new £6 million fund to support survivors of domestic abuse [Internet]. London: Greater London Authority; [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.london.gov.uk/media-centre/mayors-press-release/mayor-announces-new-%C2%A36-million-fund-to-support-survivors-of-domestic-abuse

[93] JSNA Hub. Demographics [Internet]. London: Camden and Islington Public Health; [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://jsna.camden.gov.uk/reports/demographics/

[94] Government Analysis Function. Review of disability data harmonised standards: findings from phase 2 of our research [Internet]. London: Government Analysis Function; 2025 Jul 17 [cited 2025 Oct 10]. Available from: https://analysisfunction.civilservice.gov.uk/policy-store/review-of-disability-data-harmonised-standards-findings-from-phase-2-of-our-research/

[95] Camden Council. Camden care leavers awarded protected characteristic status as council announces free Wi-Fi package [Internet]. London: Camden Council; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://news.camden.gov.uk/camden-care-leavers-awarded-protected-characteristic-status-as-council-announces-free-wi-fi-package/

[96] We Make Camden. State of the Borough 2024 [Internet]. London: We Make Camden; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.wemakecamden.org.uk/state-of-the-borough-report/

[97] Office for National Statistics. Quality of Census 2021 gender identity data [Internet]. Newport: ONS; 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/genderidentity/articles/qualityofcensus2021genderidentitydata/2023-11-13

[98] London Datastore. Modelled estimates of recent births [Internet]. London: Greater London Authority; [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/modelled-estimates-of-recent-births

[99] Department for Education. Children looked after in England including adoption: 2023 to 2024 [Internet]. London: GOV.UK; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/children-looked-after-in-england-including-adoption-2023-to-2024

[100] End Violence Against Women Coalition. Violence Against Women and Girls: Snapshot Report [Internet]. London: EVAW; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.endviolenceagainstwomen.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Violence-Against-Women-and-Girls-Snapshot-Report-FINAL-1.pdf

[101] National Audit Office. Government’s efforts to address violence against women and girls have not yet improved outcomes for victims [Internet]. London: NAO; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.nao.org.uk/press-releases/governments-efforts-to-address-violence-against-women-and-girls-have-not-yet-improved-outcomes-for-victims/

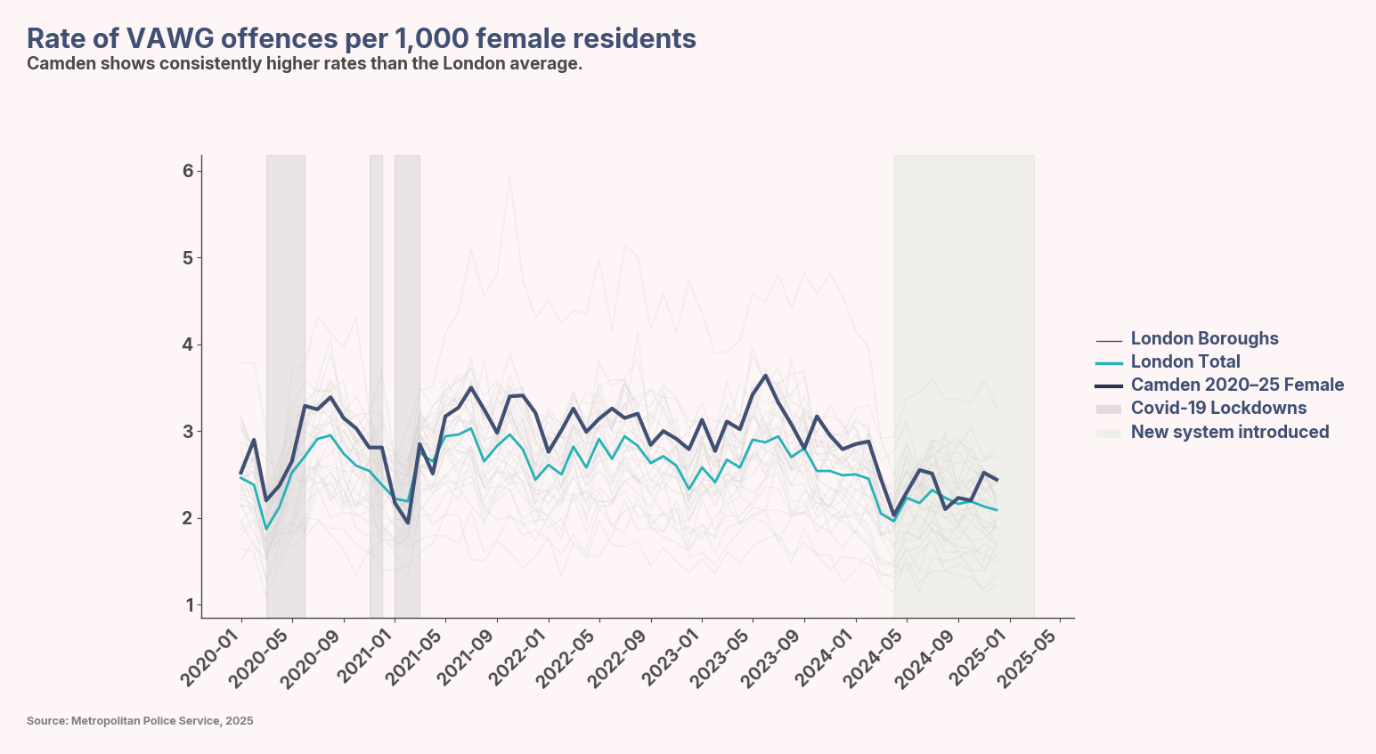

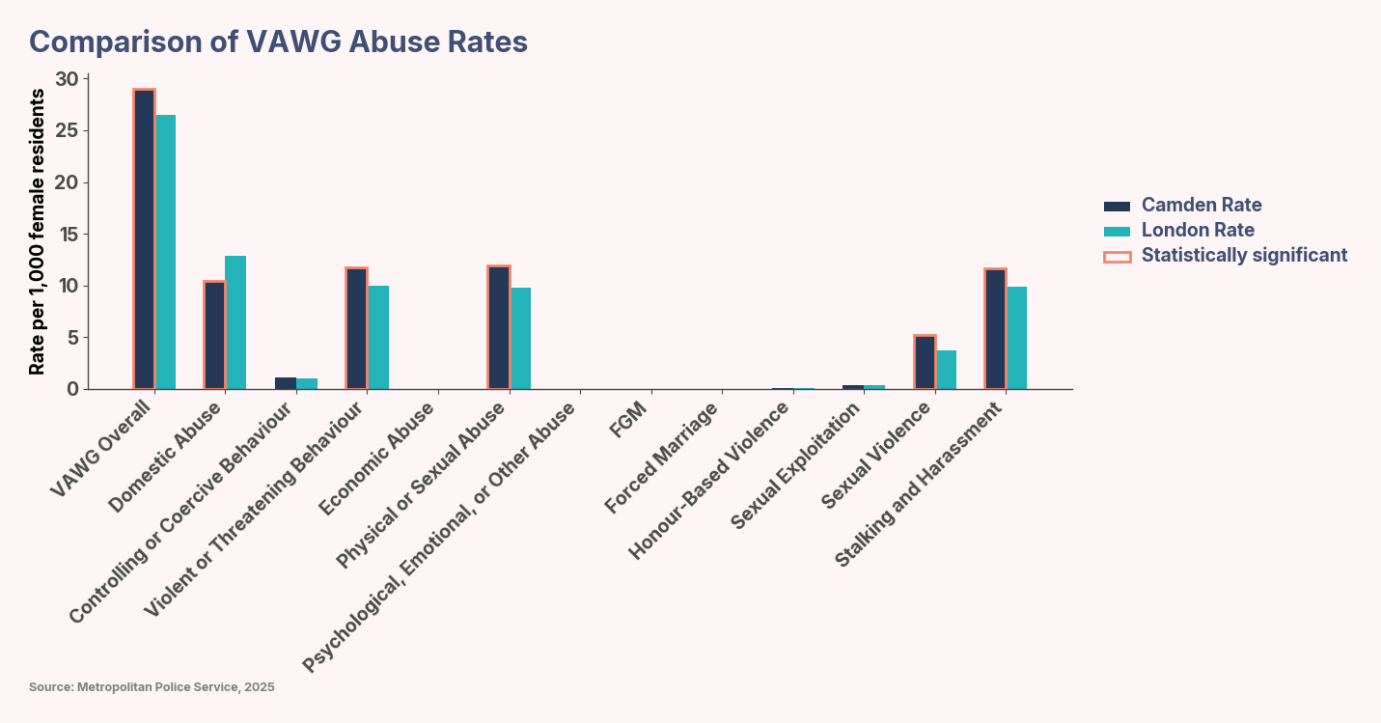

[102] A two‐proportion z‐test comparing Camden’s 2024 female‐resident offence rate (29.05 per 1,000) to that of the rest of London (26.46 per 1,000, excluding Camden) yielded a test statistic of Z = 5.47 and p < 0.0001. This difference of 2.59 offences per 1,000 residents is both statistically and practically significant: the 95% confidence interval for the rate difference is [1.63, 3.57] per 1,000, which lies entirely above zero. In other words, we can be 95% confident that Camden’s true offence rate exceeds that of the rest of London by between 1.63 and 3.57 crimes per 1,000 female residents in 2024.

[103] BBC News. Violence against women and girls rises in London [Internet]. London: BBC; 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cx2g52294xzo

[104] BBC News. Violence against women and girls rises in London [Internet]. London: BBC; 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cx2g52294xzo

[105] Women’s Aid. How common is domestic abuse? [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.womensaid.org.uk/information-support/what-is-domestic-abuse/how-common-is-domestic-abuse/

[106] Office for National Statistics. Domestic abuse prevalence and trends, England and Wales [Internet]. Newport: ONS; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabuseprevalenceandtrendsenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2024

[107] Office for National Statistics. Domestic abuse victim characteristics, England and Wales [Internet]. Newport: ONS; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabusevictimcharacteristicsenglandandwales/latest

[108] See footnote 105

[109] SafeLives. Dash risk assessment resources for professionals [Internet]. SafeLives; [cited 2025 Oct 09]. Available from: https://safelives.org.uk/resources-for-professionals/dash-resources/

[110] Surviving Economic Abuse. Economic Abuse: A Global Perspective [Internet]. London: SEA; 2022 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://survivingeconomicabuse.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/SEA_Economic-Abuse-A-Global-Perspective.pdf

[111] Refuge. Know Economic Abuse Report 2020 [Internet]. London: Refuge; 2020 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://refuge.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Know-Economic-Abuse-Report-2020.pdf

[112] Surviving Economic Abuse. SEA-EJP Evaluation Framework [Internet]. London: SEA; 2020 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://survivingeconomicabuse.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/SEA-EJP-Evaluation-Framework_112020-2-2.pdf

[113] Women’s Budget Group. Distribution of money within the household and current social security issues for couples in the UK [Internet]. London: WBG; 2020 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.wbg.org.uk/publication/distribution-of-money-with-in-the-household-and-current-social-security-issues-for-couples-in-the-uk/

[114] London Metropolitan University. Understanding the economics of abuse: an assessment of the economic abuse definition within the Domestic Abuse Bill [Internet]. London: London Metropolitan University; 2020 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://repository.londonmet.ac.uk/6307/

[115] Office for National Statistics. Partner abuse in detail, England and Wales [Internet]. Newport: ONS; 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/partnerabuseindetailenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2023

[116] NSPCC Learning. Emotional abuse: statistics briefing [Internet]. London: NSPCC; [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/research-resources/statistics-briefings/emotional-abuse

[117] Femicide Census. Homepage [Internet]. London: Femicide Census; [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.femicidecensus.org/

[118] National Police Chiefs’ Council. Violence Against Women and Girls [Internet]. London: NPCC; [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.npcc.police.uk/our-work/violence-against-women-and-girls/

[119] Femicide Census. 2000 Women: Full Report [Internet]. London: Femicide Census; 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.femicidecensus.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/2000-Women-full-report.pdf

[120] Femicide Census. Femicide Census – Profiles of women killed by men [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.femicidecensus.org/

[121] Metropolitan Police. Homicide Dashboard [Internet]. London: Metropolitan Police; [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.met.police.uk/police-forces/metropolitan-police/areas/stats-and-data/stats-and-data/met/homicide-dashboard/

[122] Vulnerability Knowledge and Practice Programme (VKPP). Domestic Homicides and Suspected Victim Suicides 2020-2023: Year 3 Report [Internet]. 2024 Mar [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.vkpp.org.uk/assets/Files/Domestic-Homicides-and-Suspected-Victim-Suicides-2021-2022/Domestic-Homicides-and-Suspected-Victim-Suicides-Year-3-Report_FINAL.pdf

[123] NHS Digital. Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) – Summary: April 2023 to March 2024 [Internet]. Leeds: NHS Digital; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://files.digital.nhs.uk/73/515589/Female%20Genital%20Mutilation%20%28FGM%29%20-%20Summary%20-%20April%202023%20to%20March%202024.pdf

[124] See footnote 120

[125] Trust for London. Prevalence of Female Genital Mutilation in England and Wales: National and local estimates [Internet]. London: Trust for London; [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://trustforlondon.org.uk/research/prevalence-female-genital-mutilation-england-and-wales-national-and-local-estimates/

[126] Home Office. Forced Marriage Unit statistics 2023 [Internet]. London: GOV.UK; 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/forced-marriage-unit-statistics-2023/forced-marriage-unit-statistics-2023#forced-marriage-unit-statistics

[127] Office for National Statistics. Stalking findings from the Crime Survey for England and Wales [Internet]. Newport: ONS; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/datasets/stalkingfindingsfromthecrimesurveyforenglandandwales

[128] Office for National Statistics. Crime in England and Wales: Year ending December 2024 [Internet]. Newport: ONS; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/crimeinenglandandwales/yearendingdecember2024

[129] National Police Chiefs’ Council; College of Policing. National Policing Statement 2024 for Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) [Internet]. 2024 Jul [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://news.npcc.police.uk/resources/vteb9-ec4cx-7xgru-wufru-5vvo6

[130] Desai R, Bandyopadhyay S, Zafar S, Bradbury-Jones C. The experiences of post-separation survivors of domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from a qualitative study in the United Kingdom. Violence Against Women. 2022;30(9):2128–47. doi:10.1177/10778012221142914

[131] Office for National Statistics. Domestic abuse victim characteristics, England and Wales [Internet]. Newport: ONS; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabusevictimcharacteristicsenglandandwales/latest

[132] NHS. Domestic abuse in pregnancy [Internet]. London: NHS; 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/pregnancy/support/domestic-abuse-in-pregnancy/

[133] Office for National Statistics. Domestic abuse victim characteristics, England and Wales: Year ending March 2024 [Internet]. Newport: ONS; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabusevictimcharacteristicsenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2024

[134] Youth Endowment Fund. Preventing violence against girls and women [Internet]. London: Youth Endowment Fund; [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://youthendowmentfund.org.uk/preventing-violence-against-girls-and-women/

[135] Johnson R. Domestic abuse rates for Year 5 and Year 6 in Camden primary schools [internal report]. Camden Council; 2024 Feb 8.

[136] Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. Systems-wide evaluation of homelessness and rough sleeping: preliminary findings [Internet]. London: GOV.UK; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/systems-wide-evaluation-of-homelessness-and-rough-sleeping-preliminary-findings/systems-wide-evaluation-of-homelessness-and-rough-sleeping-preliminary-findings

[137] Camden Council. Section 42 enquiry: The four-stage process [Internet]. London: ASC Practice; 2023 Mar 15 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://ascpractice.camden.gov.uk/what-matters-to-people/safeguarding/safeguarding-duties-and-procedures/section-42-enquiry-the-four-stage-process/#main

[138] London City Hall. Supporting victims and witnesses [Internet]. London: Greater London Authority; [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.london.gov.uk/programmes-strategies/mayors-office-policing-and-crime/services-we-fund/supporting-victims-and-witnesses

[139] Metropolitan Police. Tackling perpetrators: VAWG action plan summer 2024 updates [Internet]. London: Metropolitan Police; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.met.police.uk/police-forces/metropolitan-police/areas/about-us/about-the-met/vawg-action-plan-summary/tackling-perpetrators/

[140] Waxman C. Only 40 percent of London crimes reported as victims despair of justice. The Times [Internet]. London: The Times; 2025 Jul 15 [cited 2025 Oct 7].

[141] South West Londoner. Domestic abuse incidents remain high in London [Internet]. London: South West Londoner; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.swlondoner.co.uk/life/03122024-domestic-abuse-incidents-remain-high-in-london

[142] Domestic Abuse Housing Alliance (DAHA). What is DAHA Accreditation? London: DAHA. Available from: https://www.dahalliance.org.uk/membership-accreditation/what-is-daha-accreditation/

[143] Camden Council. Cabinet meeting documents: 18th January 2023. London: Camden Council; 2023. Available from: https://camden.moderngov.co.uk/ieListDocuments.aspx?CId=122&MId=10174&Ver=4

[144] Home Office. Domestic Abuse Act 2021: statutory guidance. London: GOV.UK; 2022. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/domestic-abuse-act-2021

In the CSN risk indicator checklist, among the 611 workflows where a risk form was completed, 38.0% indicated that the individual, or someone they know, had been threatened with being killed by the abuser.

In the CSN risk indicator checklist, among the 611 workflows where a risk form was completed, 38.0% indicated that the individual, or someone they know, had been threatened with being killed by the abuser.

Early intervention and prevention opportunities

Early intervention and prevention opportunities